top architecture design thesis 2020

RV COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE

BENGALURU, INDIA

Design thesis authored by

Disha Dharesh Kumar R

share

THESIS SPECIFICATIONS

Thesis Title : Jenu Goodu

Location : Buffer Zone, Nagarahole Tiger Reserve, Karnataka, India

Project type: Re-housing Tribal Communities

Year of completion : 2020

Name of Thesis mentor: Anup Naik, Mehul Patel, Nagaraj Vastarey, U Seema Maiya

Proposition

Key words and associations: indigenous, tribal, ritual practices, jenu- honey, goodu- nest, indigenous typology, sacred and ritual space, nature, communities’ social space, tectonics, hands on skill development for construction, learning space

“As Leo Frobenius puts it, archaic man plays the order of nature as imparted on his consciousness… [he] thinks man first assimilated the phenomena of vegetation and animal life and then conceived an idea of time and space, of months and seasons, of course of the sun and moon. And now he plays this great processional order of existence in a sacred play, in and through which he actualizes a new or ‘recreates’, the events represented and thus helps to maintain the cosmic order. Frobenius draws even more far-reaching conclusions from this ‘playing at nature’.”

–By J. Huizinga (historian and cultural theorist), Book ‘Homo Ludens’

This ‘play’ gets reflected in art, crafts, music, lifestyle which in turn reflects on architecture of the indigenous (tribal communities). It can be further argued that if these signs and symbols (derived from enactment of rituals and practices) are not considered then architecture would be meaningless and unrelatable.

This architectural thesis explores how ‘dwelling’ spaces for the displaced tribal can be designed as a community driven initiative. Thus, it helps the community thrive and gives them an opportunity for self- expression. This thesis studies indigenous worldview, practices, skills, methods and uses them to evolve building practices that are traditional on one end but innovative to add to the skill set, and looks at creating a co-operative that helps them build and learn. It re-interprets and re-imagines spaces for indigenous communities. It attempts to create a dialogue between indigenous settlers and the world outside, rather than an invasive introduction of the outside practices and culture.

Premise or Background

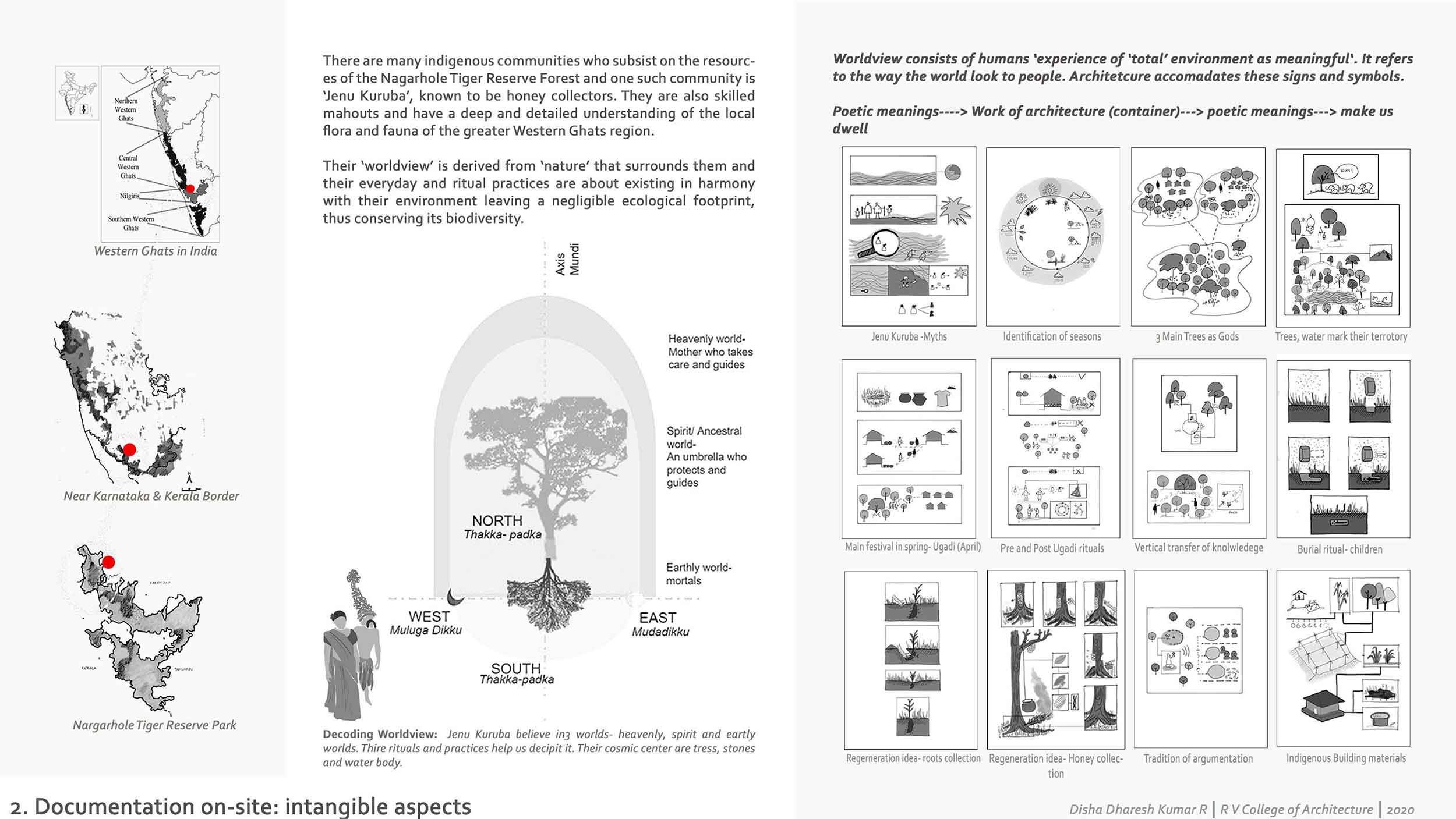

This project is situated in the buffer zone of Nagarhole Tiger Reserve Park (NTRP) in Karnataka, India. There are many indigenous communities who subsist on the resources of the forest in the fringes and one such community is ‘Jenu Kuruba’, known to be honey collectors. They are also skilled mahouts and have a deep and detailed understanding of the local flora and fauna of the greater Western Ghats region. Their ‘worldview’ is derived from ‘nature’ that surrounds them and their everyday and ritual practices are about existing in harmony with their environment leaving a negligible ecological footprint, thus conserving its biodiversity.

But in the last two decades, natural habitats within and around forest reserves and sanctuaries have been destroyed due to increased demand for natural forest resources and developmental pressures due to urbanization have led to buildings creeping into the fringe areas. Hence with the view towards ‘conservation’, the Government has prohibited any habitation within these areas. This has led to the resettlement and rehabilitation of many indigenous communities in and around Nagarhole TRP under the State Government Schemes, funded by the World Bank in Karnataka. But most resettlement schemes ignore the needs and fail to understand the association the communities have with nature instead imposing ‘outside/ non-local’ typologies alien to them. Hence this thesis challenges the conventional top-down planning and design practices for housing provided by the Government. Instead, it proposes that an in-depth understanding of world views, community practices, and relationships with natural systems is integral to conceiving or envisioning the design process.

Design Approach

Site: The area proposed for rehabilitation in the fringe area is currently barren (no vegetation, water source) with minimum or no infrastructure facilities to support a settlement. But for indigenous communities, the organization of territory, land on which they move is architecture. The project looks at restructuring the unproductive land/ site by integrating with the existing green and blue networks (vegetation, water and terrain) to make it a part of the forest landscape in the long run.

Settlement: The project proposes a clustered organization of built and open spaces (dwelling units, community spaces, learning areas, burial ground) in sync or harmony with traditional ritual and everyday practices. It considers the future aspirations of the indigenous community and provides an opportunity to collaborate with the world outside by the addition of learning spaces for vocational training and school for learning new skills.

Crafting built forms (material and tectonics):

“there is a very fundamental difference between someone who commissions a house to be constructed, and one who actually builds it with his own hands. The builder of the latter types of dwelling has different needs and expectations, and his house therefore displays an integrated pattern values, whereas one which is built by an architect imposes elements which are not the patron’s and therefore it becomes a blueprint for living rather than the reflection of a life style”

–Caroline Stanley, Talk ‘Bamboo dwellings in a Concrete age-architecture of the hill tribes of South India, 1984

Construction for the indigenous peoples is a social activity (relationship) related to the ‘identity’ of family that fosters community building/ partnerships. Hence this project believes that involving or engaging in the process of design and construction would give them a sense of belonging, pride and help in their poetic involvement with the surroundings. It encourages building with local natural (sustainable) materials like bamboo, grass, mud. It also looks at evolving indigenous building knowledge and skills to craft each structure or built form. But it also introduces skills like carpentry, pottery making, honey testing that would add value to the community. Based on the changing requirements or activities or spirations, the community can adapt and innovate these construction practices to add new structures to the cluster. Over time the settlement will gradually assimilate with the new blue and green systems planned and be an extension of the ‘forest’.

“As long as communities recognizes their essential incompleteness, they will remain open to dialogue and reinvention, to fluid transactions with the world beyond, and will be able to shape a future for themselves as free agents”

–K. V. Subanna (Kannada writer, dramatist and founder of NINASAM drama institute)

Conclusion

The project firmly believes that the role of an architect is to understand indigenous community practices and their connection with nature thus facilitating the poetic involvement of the people with their surroundings. Only then will a ‘work of architecture’ make a difference or matter to them in some way. Thus, the bottom-up approach of participatory design is important for sustaining communities with a knowledge base that has little or no recorded history (oral traditions). This would invariably create an awareness to the indigenous communities that their knowledge and skills are precious and should not be easily overthrown in the name of ‘progress’ or ‘civilization’. Architecture should build bridges that help indigenous communities communicate with the world outside.

the end

Copyright information: ©️ Student author 2020. Prior written authorization required for use.

Request permissions: If you wish to use any part of the documentation forming part of the undergraduate thesis submitted to DSGN arcHive, please seek prior permission from the concerned student author through the respective college/university.

Exclusion of liability: DSGN arcHive and its owner do not undertake any obligation to verify the ownership of any content submitted for publication/broadcast on this website and shall not be liable for any infringement of copyright by, or unauthorized use of, such content.

HOMEPAGE

Copyright © 2026 DSGN arcHive